By Jorge Azama

Today, with the increasingly widespread development of so-called “Immersive Audio,” one of the terms that is constantly talked about, and that could confuse newcomers to the subject, is “Ambisonic(s).” This term comes from the prefix “ambi” (which means “around”) and the word “sonic(s)” (which means “belonging or relating to sound”).

In this article, we will review the history of this technology and talk about some technical aspects related to its use in creating immersive audio material.

The “Ambisonic” technique is one that allows recording and reproducing audio in a 360° sonic sphere, in such a way that the listener not only receives signals from the front (as in a conventional stereo system) but from all directions, which causes them to feel “immersed” in said sound experience (hence the term “immersive audio”).

This technology, widely used today, has its origins in the mid-70s, when a group of British scientists from the Universities of Oxford and Reading, led by Professors Michael Gerzon, Peter Fellgett and Geoffrey Barton, dedicated themselves to the idea of designing a system capable of recording and reproducing sound material that could give the sensation of direction, distance and height of the recorded sound, using 4 audio channels (as an extension of the stereophonic technique called “Mid/Side” or “M/S”, patented by Alan Blumlein in 1931).

It is worth mentioning that Michael Gerzon was the author of more than 120 research papers on Spatial Audio Recording and Reproduction, Signal Processing, Noise Modeling, etc., being often described as “one of the greatest thinkers and writers in the audio industry”, having received the Fellowship Award from the Audio Engineering Society – AES in 1978, as well as the Gold Medal (the highest recognition awarded by the AES) in 1991.

The bases of the Soundfield microphone and Gerzon’s Ambisonic theory were generated at the OUTRS (Oxford University Tape Recording Society), in the period between 1967 and 1972, making its first tetrahedral recording in May 1971.

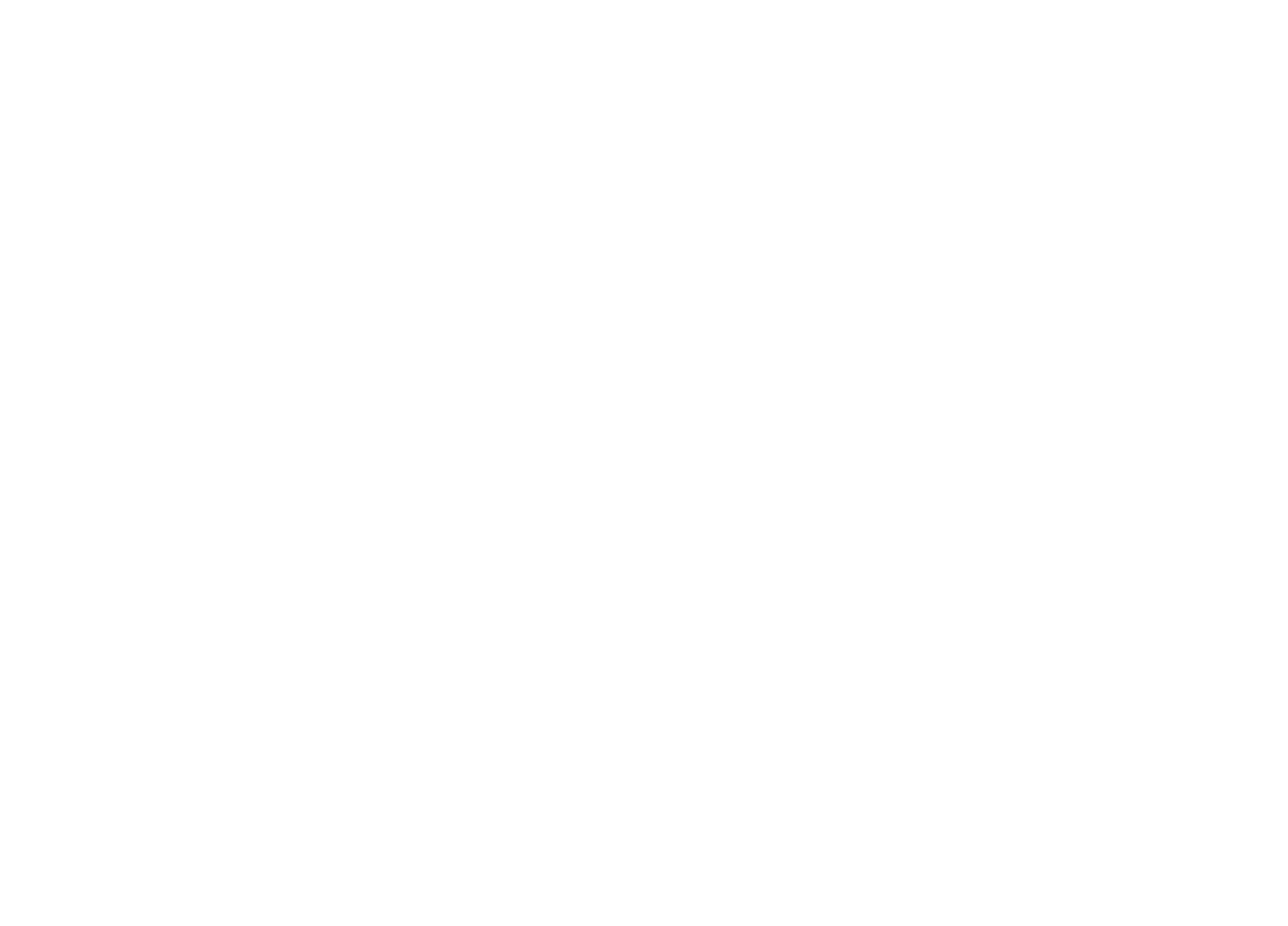

Tetrahedral arrangement, with 4 Calrec microphones, developed by the OUTRS.

(Photo: Stephen Thompson)

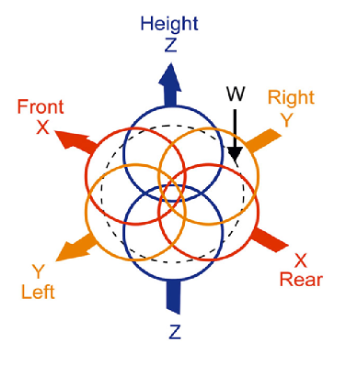

One of the most important contributions of Gerzon, together with Dr. Peter Craven, was designing and building a microphone specially created for this purpose, which they would call “Soundfield”, carrying out in October 1975 the demonstration of the first prototype of said microphone to the members of the OUTRS, using capsules manufactured by the company Calrec for its construction. Thanks to this, Gerzon continued working on successive prototypes with engineers Ken Farrar and Clement Beaumont, who worked for Calrec, until said company officially launched the first model of the Soundfield microphone on the market in 1978. Said microphone contains 4 microphone capsules, perfectly aligned, in a tetrahedral arrangement. The reason for using 4 capsules comes from the following criterion: 2 points define a line (one dimension); 3 points define a plane (2 dimensions); 4 points define a volume (3 dimensions in space). Acoustics experts define the operation of the Soundfield microphone as a “decomposition of the spherical harmonic sound field”, which means that for a minimum representation in 3 dimensions we need at least 4 microphones, which give us “4 spherical harmonics”.

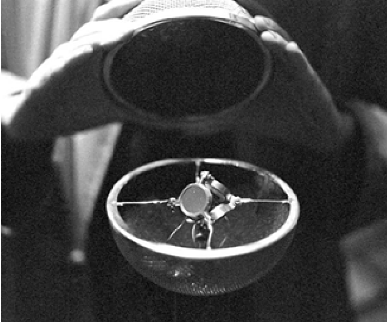

Close-up image of the tetrahedral composite capsule of the Calrec Soundfield microphone, with 4 diaphragms.

(Photo: Steve Thornton)

Peter Craven (left) and Michael Gerzon (right) with the 1st prototype of the Soundfield microphone made by Carlec in 1976.

(Photo: Steve Thornton)

Schematic diagram of the alignment of three-dimensional sound capture in space.

Historically, the battle for the then-called “Surround Sound” was fought in the 70s between “Ambisonic” and “Quadraphonic” (a system in which 4 discrete speakers were used for the sound reproduction of 4 different audio channels, which had the German experimental musician Karlheinz Stockhausen as one of its greatest supporters, and later the mythical band Pink Floyd). It is even said that Gerzon was very close to closing an agreement with Ray Dolby (founder of Dolby Labs), who at that time was looking to license some “surround sound” format. Unfortunately, for reasons beyond Gerzon and Dolby, that deal never materialized.

Another curious fact is a quote attributed to Peter Craven, who said the following in the mid-70s: “What Michael (Gerzon) does now, will be appreciated by the world in about 30 years”. And Craven was absolutely right.

Gerzon’s Ambisonic theory remained a poorly understood and marginally used system for decades, until the near present. Its ability to capture and represent a 360° spherical sound field has made it a natural choice for Virtual Reality (VR). Currently, listeners can be immersed in a dynamic sound environment using headphones, which is why many content distribution platforms such as YouTube, Facebook and some others have adopted Ambisonic Sound as their preferred format.

In addition, there are currently several manufacturers worldwide that offer ambisonic microphones, with the same basic operating principle as the Soundfield, which reaffirms the current importance of this technology thanks to applications such as Virtual Reality.

Various current options for ambisonic microphones on the market.

From left to right: Soyuz 013 from Soyuz Microphones; Spatial Mic from Voyage Audio; NT-SF1 from Røde and Ambeo VR Mic from Sennheiser

AMBISONIC FORMATS: “A-FORMAT” AND “B-FORMAT”

Format A (“A-Format”) and Format B (“B-Format”) are the 2 analog audio standards that are part of the Ambisonic workflow.

Format A (A-Format): this is the name given to the unprocessed (“raw”) recording of the 4 individual tetrahedral cardioid capsules in an ambisonic microphone. Because each manufacturer’s microphones have different capsules at slightly different distances, this format is somewhat specific to each microphone model.

Format B (B-Format): This is a standardized format derived from Format A, which consists of 4 channels. The first channel contains the amplitude information of the signal, while the others determine the directionality through phase relationships between each of the signals. This format can then be decoded to be heard on different systems, such as headphones or home theater systems. There are many ambisonic tools to combine and alter the signals in this format. Due to the latter, within Format B there are also 2 standards, namely:

- Furse – Malham (FuMa): Old standard (named in honor of professors Richard Furse and Dave Malham from the University of York), which is still compatible with a wide variety of plug-ins and other ambisonic processing tools. In this case, the 4 channels are called “WXYZ”.

- AmbiX: Modern standard that has been widely adopted by content distribution platforms, such as YouTube. The order of the channels in AmbiX is “WYZX”.

HIGHER ORDER AMBISONICS

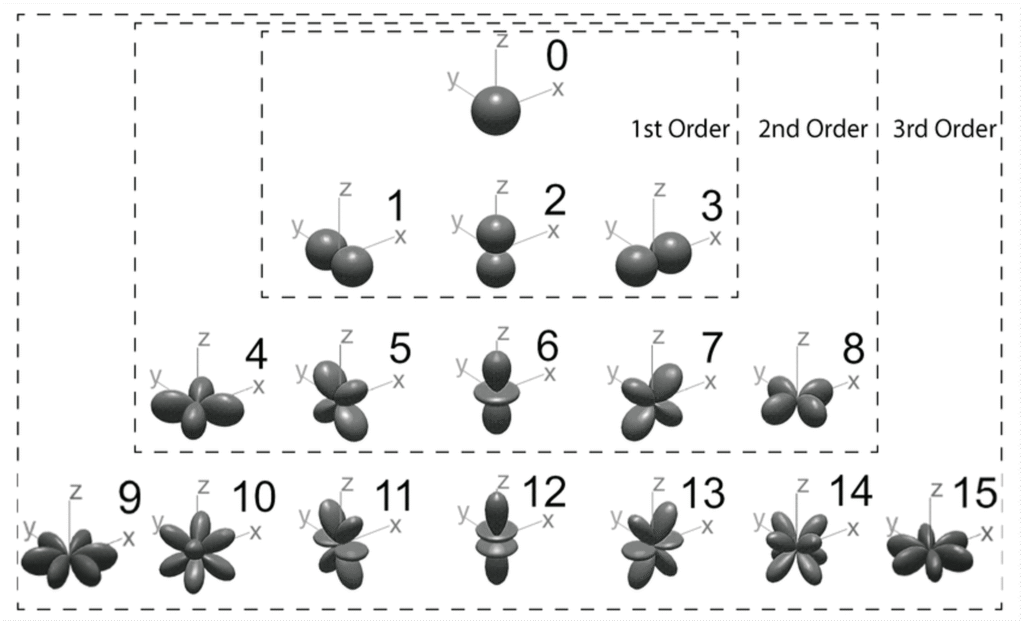

The so-called Higher Order Ambisonics (HOA), are those in which not only 4 microphones or signals are used to translate them to Format B and make the decomposition of the spherical harmonic sound field, but more than 4 are used to obtain a more precise representation. Said “precision” is obtained by increasing the order of the spherical harmonic sampling, according to the following table:

| Ambisonic Order | # of Spherical Harmonics |

| 1st | 4 |

| 2nd | 9 |

| 3rd | 16 |

Finally, it is important to mention that, regardless of the format in which you deliver your ambisonic files, it is vital to take into account the standards you are using in your chain and make the necessary conversions when appropriate. Otherwise, the rotations and movements will end up in the wrong direction and the entire sound sphere will end up a mess.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

– Arteaga, Daniel – “Introduction to Ambisonics” (2025)

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280010078_Introduction_to_Ambisonics

– Ambisonics.info – “Ambisonics” (2017)

https://ambisonic.info/ambisonics.html

– Anderson, Joseph – “The Ambisonic Technique” (2010)

– Rode Microphones – “The Beginner’s Guide to Ambisonics” (2022)

https://rode.com/en-au/about/news-info/the-beginners-guide-to-ambisonics

– Santos, Claudio – “VR Audio — Differences between A Format and B Format” (2017)

– University of Oxford – “Into the Soundfield: Michael Gerzon and Ambisonics at Oxford” (2018)

https://intothesoundfield.music.ox.ac.uk

About the author:

Jorge Azama is a Technical Professional in Sound Engineering, graduated with honors in 1998 from the Orson Welles Higher Technological Institute (Lima, Peru). Member of the Audio Engineering Society (AES) since 2003 and one of the founders of the AES Peru Section in 2004. Between 2018 and 2021 he was the Vice-Chair of AES Peru. In 2019 he was the Chair of the Latin American Conference of the Audio Engineering Society, held in Lima. For this reason, in 2020 he received the AES Board of Governors Award. He has been Regional Vice-President of AES for Latin America (the highest position in the region), in the period 2022-2025.

He has extensive experience in both Live Sound and Studio Recording and Mixing, having worked with national and foreign artists of various musical genres.

He has given conferences, talks, workshops, seminars, master classes and webinars at various international professional audio events in countries such as: Uruguay, Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, Argentina, Panama, Haiti, Brazil, United States, Chile, Spain, Venezuela, Guatemala, Mexico, Honduras and Peru.

He currently works as a Professor at the Peruvian University of Applied Sciences (UPC), in the Musical Production Specialty; and at the Orson Welles Higher Technological Institute, in the Technical Careers in Sound Engineering and Musical Production.